Research

What is analogue gravity?

In the words of Richard Feynman,

The same equations have the same solutions.

The Feynman Lectures of Physics: Volume II

This is the central maxim of analogue gravity. It is the art and science of identifying the maps between the fundamental equations of two distinct systems and concluding that if a phenomenon occurs in the first, it could also in the second.

Analogue gravity first began in 1981, when William (Bill) Unruh was teaching a course on fluid mechanics. He envisioned a scenario, where two fish were communicating through sound waves in water. Bill realised that if the water flowed faster than the speed of sound in the fluid, the fish would be unable to hear each other, as the sound waves would be swept away by the flowing water.

Bill used this insight and identified an analogy between the speed of sound in water and the speed of light in our Universe. Going further still, Bill realised that supersonic fluid flow is analogous to a black hole—if the water flows faster than the speed of sound, it creates a region from which sound waves cannot escape, much like how light cannot escape from a black hole. This marked the birth of analogue gravity, where fluid systems are used to model and study aspects of curved spacetime and event horizons.

Analogue gravity has come a long way since 1981. It is no longer just a subfield of quantum field theory or general relativity but has grown into a discipline in its own right. Several of the predictions at the interface between general relativity and analogue gravity such as superradiance and the stimulated Hawking effect have even been observed in these analogue spacetimes.

Analogue gravity has expanded beyond classical fluid systems to include a variety of quantum and optical systems, such as superfluid helium, Bose-Einstein condensates, and optical fibres. The low temperatures of these quantum systems allow us to probe regimes that mimic the emptiness of a quantum vacuum and by engineering light pulses, we can mimic the causal structure of black holes in optical analogues. This diverse range of experimental platforms has enriched the field and enabled the study of quantum field theoretic phenomena in a controlled laboratory setting.

Analogue black hole in the Black Hole Laboratory, University of Nottingham Credit: The Guardian

Depiction of an analogue black hole for a NewScientist article in part inspired the Black Hole Laboratory, University of Nottingham

PhD research

My PhD research focused on a fundamental prediction of quantum field theory: the Unruh effect. In a nutshell, the Unruh effect states that if two observers exist in an otherwise empty universe—one moving at constant speed and the other accelerating uniformly—the accelerating observer perceives a thermal bath of particles that the inertial observer does not. The temperature of this thermal bath is directly proportional to the observer’s acceleration.

There has been no direct experimental verification of the Unruh effect to date, though experimental confirmation retains broad interest due to the effect’s relation to the Hawking effect and quantum effects in the Early Universe that led to the large structures we see today.

The original formulation of the Unruh effect assumed an infinite Universe with a background temperature of zero Kelvin and an observer accelerating forever! Any lab and any experiment must, however, take place within a finite region for a finite amount of time and there will necessarily be a nonzero background temperature. During my PhD, I investigating the interplay of experimental considerations such as thermality and confinement. Read my PhD thesis—Circular motion Unruh effect: in spacetime and in the laboratory—to find out more.

Cartoon depiction of the Unruh effect. Credit: PhD thesis of Giuseppe Gaetano Luciano

Anti-de Sitter spacetime

Famously, Einstein referred to the cosmological constant Λ as his “biggest blunder;” however, this extra term in his field equations led to the discovery of many more spacetimes. Without a cosmological constant, the simplest spacetime is called Minkowski spacetime, describing an empty Universe with no gravity. When a cosmological constant is included, the simplest spacetimes are the de Sitter (Λ>0) and anti-de Sitter (Λ<0) spacetimes. Even in these simplest spacetimes, drastically new physics emerges compared to Minkowski spacetime.

In de Sitter spacetime, the cosmological constant acts as a form of energy with negative pressure, a type of dark energy. This negative pressure causes spacetime to expand, so de Sitter spacetime is of great interest to cosmologists.

In anti-de Sitter spacetime, the consequence of a negative cosmological constant is that light and information can reach spatial infinity in finite time; a negative cosmological constant creates a notion of spatial confinement. This very special feature of (asymptotically) anti-de Sitter spacetimes has given rise to the holographic principle and the celebrated AdS/CFT correspondence as candidates for better understanding the Universe.

More recently, I have explored the circular motion Unruh effect in anti-de Sitter spacetime, as well as thin shells of energy around an accelerating black hole in a locally anti-de Sitter spacetime known as the C-metric.

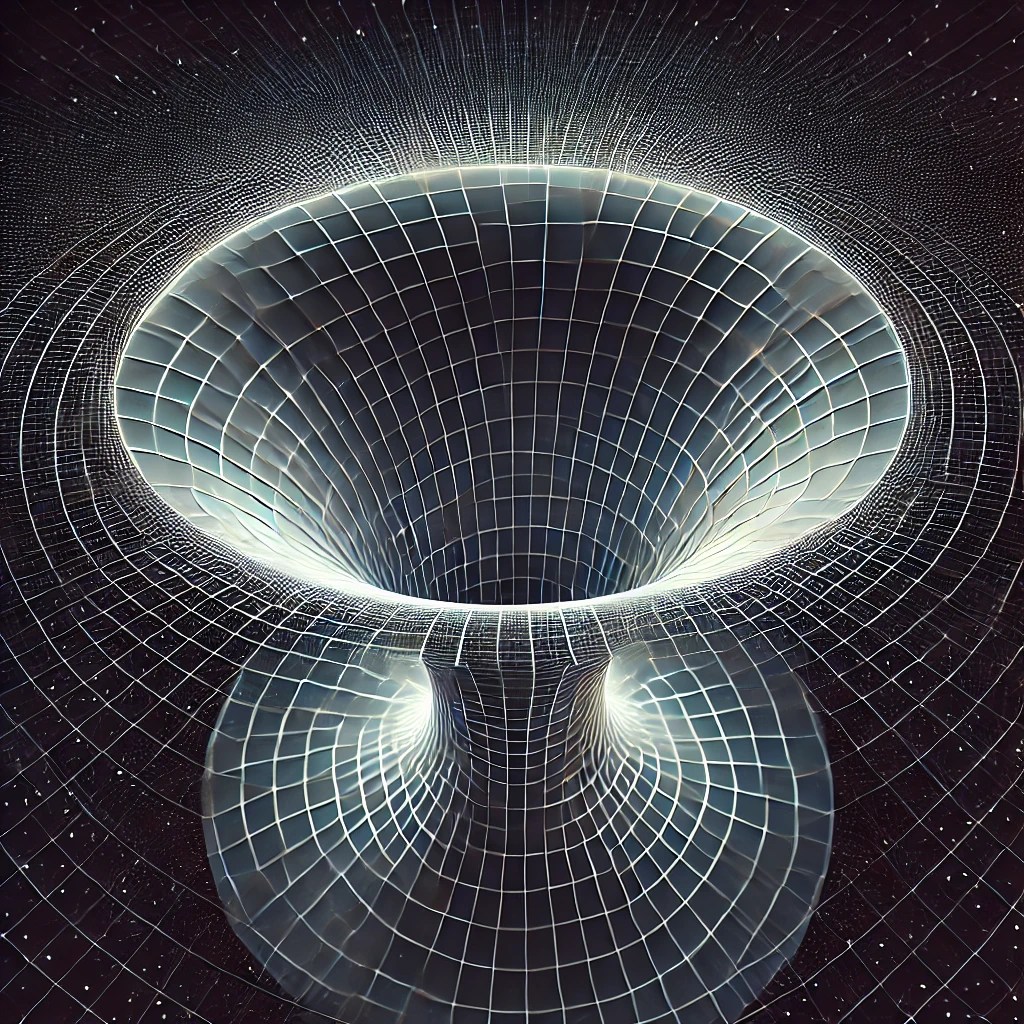

Visualisation of anti-de Sitter spacetime by AI.

GET IN TOUCH

Interested in asking me more about my research?

You can email me at: cameron.bunney [[[@]]] nottingham.ac.uk